A brief history of artistic resistance

Blackstars

We don’t often think about it this way, but the art we admire today on the walls of prestigious museums and galleries is, in essence, a chronicle of the rebellion against the opposition to innovation. Many of the aesthetic breakthroughs we now consider the bedrock of our culture were born amidst the throes of a technological scandal.

For centuries, the same pattern has repeated: a new technology emerges, promising to evolve the creative process, and the "gatekeepers of true art" - critics and established masters - immediately proclaim the death of genuine craft. But the common thread among history’s greatest creators was not a fear of the new. It was courage in the face of change. The success of artists like Jan van Eyck, Julia Margaret Cameron, or Andy Warhol stemmed from the fact that they were the first to see a new invention’s potential to express what was previously inexpressible, and they built their artistic manifestos upon that very potential.

Let us look back to the 15th century, when tempera reigned supreme in painting studios. Painting with pigment mixed with egg yolk was a tedious and unforgiving process; the paint dried almost instantly, leaving the creator no room for error and, more importantly, no way to build depth. When Jan van Eyck began to popularize oil binders, the conservative establishment looked on with disdain. Oil was seen as a "dirty" and slow technique, a mere craftsman’s compromise. However, van Eyck understood that this slowness was the key. Oil allowed him to apply dozens of translucent layers, letting light "travel" within the painting. What was dismissed as a departure from noble tradition resulted in a realism that remains breathtaking to this day. Without this rebellion against the "dictatorship of the egg," art history would never have known the soft sfumato of Leonardo da Vinci, the dramatic chiaroscuro of Caravaggio, or the psychological depth of Rembrandt - their genius required the new chemistry of oil to find its voice.

Jan van Eyck

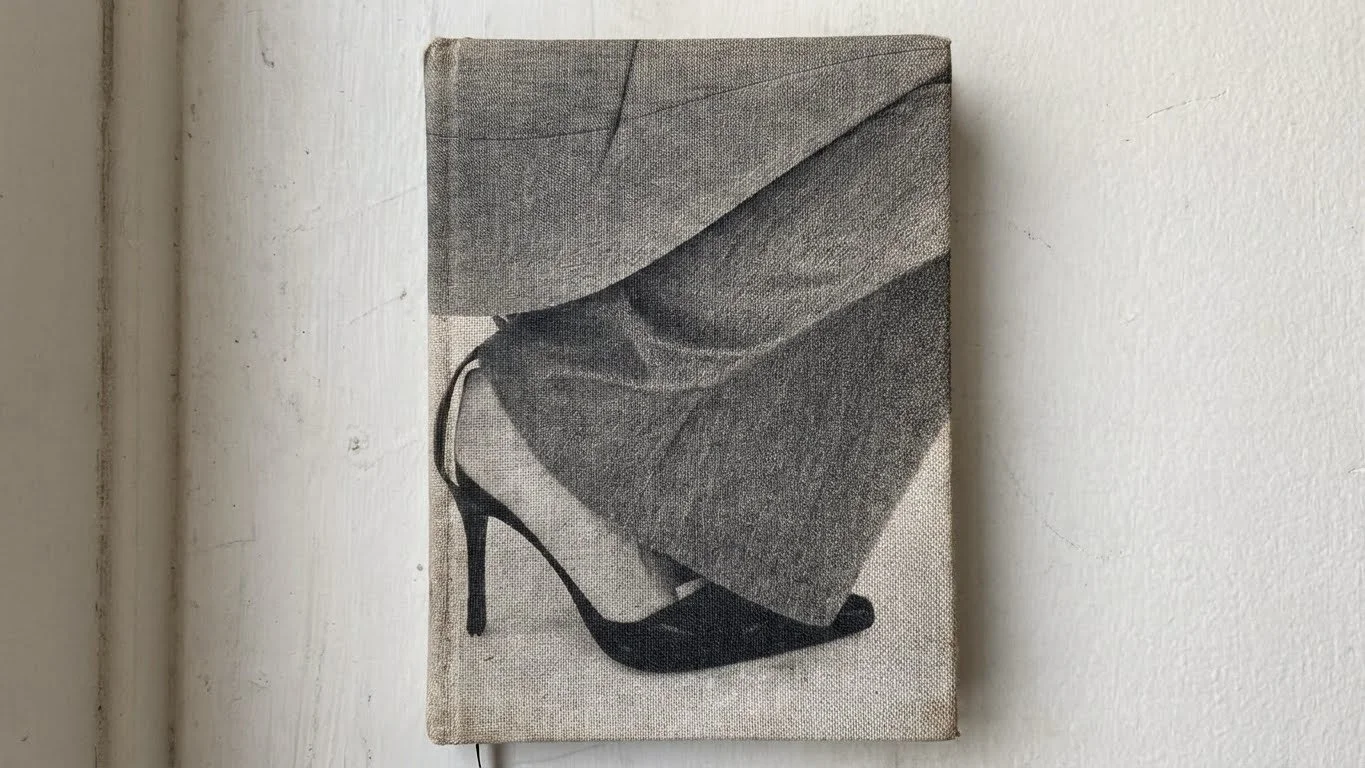

Yet the debate over the tool did not end with painting; with the arrival of the 19th century, it shifted to the ground of the emerging medium of photography. In its infancy, photography was viewed almost exclusively as a cold, scientific, and documentary tool - a "mechanical eye" meant only to ruthlessly record reality. The gatekeepers of this new technology obsessively chased absolute sharpness and technical purity. Julia Margaret Cameron, picking up a heavy camera and working with the demanding wet-collodion process, decided to break all these rules. Instead of sterile, "correct," and emotionless documents, she created portraits that were intentionally out of focus, playing with soft light and conscious movement. Her contemporary critics were merciless; they wrote that her work was "slovenly" and that she "did not know how to operate the camera." Cameron, however, was not seeking technical perfection but artistic expression - a realm reserved at the time only for painting. She understood that "error," imperfection, and softness are exactly what allow the camera to stop being a machine and start being a tool for portraying the invisible. In defiance of the technocrats of her era, she became one of the first artists to prove that photography becomes high art when it is entirely subordinated to human sensitivity.

Julia Margaret Cameron

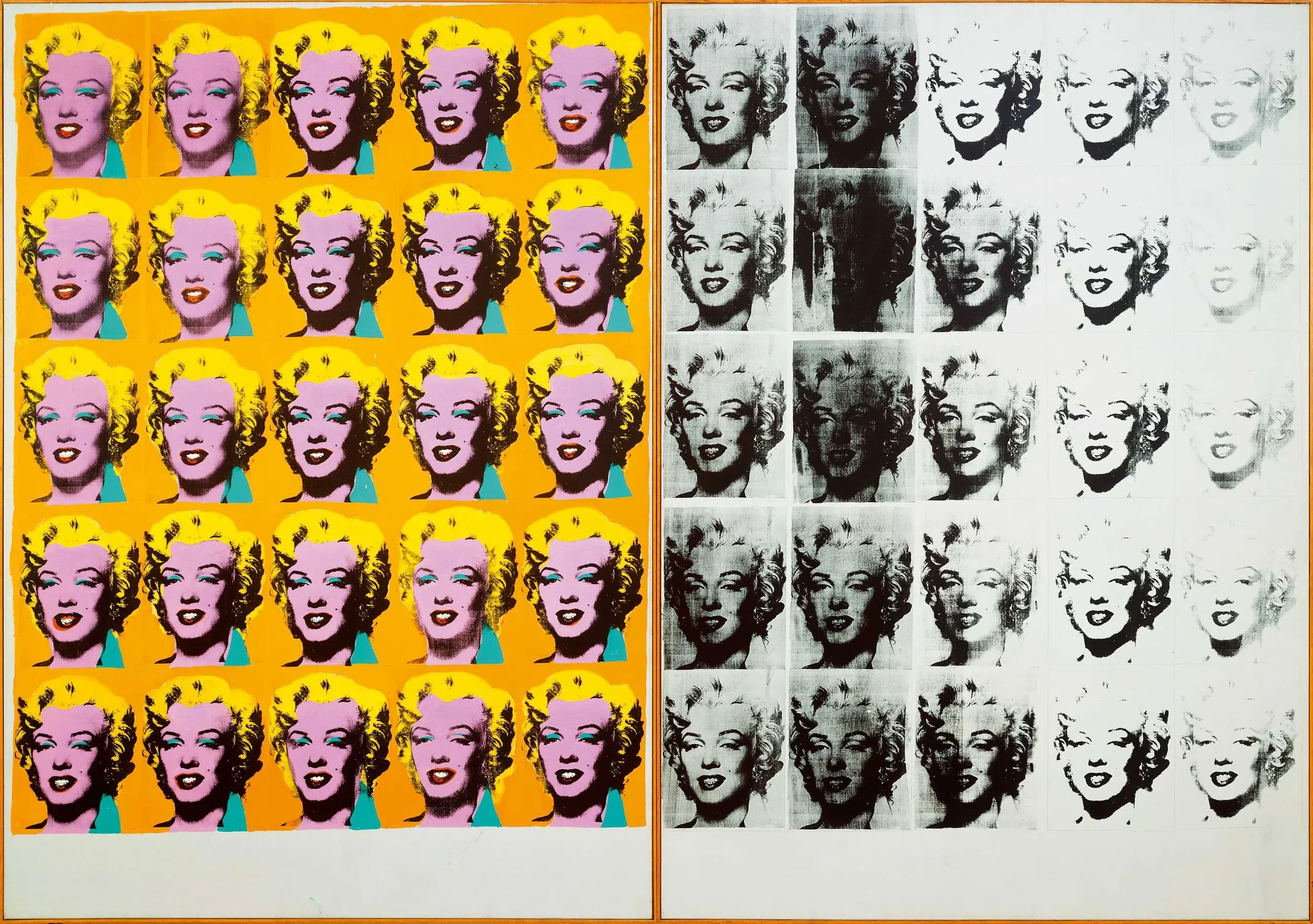

As photography eventually embraced error and emotion, the artistic rebellion had to find a new battlefield - this time in the heart of emerging mass culture. In the mid-20th century, while the art world remained firmly attached to the myth of the unique, hand-painted masterpiece, Andy Warhol introduced an industrial tool to the gallery: the commercial screen print. This technique, previously used almost exclusively for product labels and advertisements, became his way of questioning everything deemed "noble." Critics were scandalized; he was accused of ceasing to be an artist and becoming a machine operator that "simply" duplicated images. For Warhol, however, this mechanical repetition was the key to understanding a new, mass-produced reality. Rather than hiding the technical process, he deliberately exposed it - celebrating ink bleeds, misalignments, and "messy" paint layers. What purists saw as a lack of craft and a shortcut was, in fact, a brilliant artistic maneuver. Warhol proved that an artist's vision does not end at the tip of a brush, and that a machine can be a powerful ally in commenting on the human condition. By turning his studio into "The Factory," he showed that it is the creator’s intent, rather than the uniqueness of a mechanical gesture, that defines the power of the message.

Andy Warhol

Today, history comes full circle, and the screen print is replaced by code. We stand before a new frontier - computational intelligence capable of generating images in seconds. The voices of opposition sound familiar: "it’s not art," "it’s soulless," "it’s the end of craft." Yet the lesson from art history is clear - the problem is never the tool itself, but a lack of vision to harness it. What we today call sterile generative images and video is merely a transitional phase, the same as the cold documentary photography of Cameron’s time or the "vulgar" screen prints of Warhol’s. The real challenge is not to run from the algorithm, but to humanize it. To use immense computational power not to chase digital perfection, but paradoxically to find human error and emotion within it. In the hands of a conscious creator, AI becomes simply a new tool that, rather than replacing the human hand, becomes an extension of their sensitivity. Success in this new era will not belong to those who generate pixels the fastest, but to those who can breathe intent, craft, and vision into them - transforming mathematical notation into an authentic, human experience.

Blackstars